Last week, news channels announced that one of Alfred Hitchcock’s long-lost silent films, The White Shadow, had been found. Only about half of the full print exists, but it is nonetheless the earliest Hitchcock work that currently exists, and you can watch it right here on the web.

Alfred Hitchock is only one amazing director that his/her start in the silent era of filmmaking. The silent era is an amazing period of film, where the language of visual, in-motion storytelling was still being created out of nothing, and where all stories had to be told on the strength of their image. Directors who were forged in that era often went on to create sound films that birthed the golden age of filmmaking.

Some of these silent era experiments in film either did not work or do not age well; some silent filmmaking is difficult to endure even for an intrepid film nerd. However, there are a great many silent films that are fascinating, even 90 or 100 years later.

After a couple conversations I had last week about Hitchcock’s very early work, I realized that even some film fans I know aren’t very familiar with silent moviemaking. Thus, I figured it might be nice to assemble a Silent Film Primer: a list of silent films that could pique the interest of casual film fans.

Please keep in mind that the list below is not a “best of” list. It should not be judged by what it omits (“You forgot my favorite one!”). It is merely meant to be a list that highlights particularly nifty silent films that I believe would be fun for people who aren’t already familiar with very early filmmaking.

Let’s go!

METROPOLIS (1927, dir. Fritz Lang): Aside from being the great-grandmother of modern science-fiction films, Metropolis is a visual feast from beginning to end. Modern viewers might giggle at the exaggerated acting style at first, but are usually won over within minutes by the incredibly clever animations, special effects, costumes, and staging.

(When I host parties, I sometimes run a film with the sound off while people socialize, just as a sort of visual thing for people to glance at but mostly ignore. The one time I did that with Metropolis killed all the socializing dead, because everyone in the room couldn’t help but stare at the film. The visual potency of the movie is amazing.)

The themes of the film — about humanity being lost amongst machinery — also still translate into today.

One of the boons of the fame of Metropolis is that the film has been painstakingly restored, despite being heavily edited after its premiere. While there are still parts of the film missing (amounting to a couple minutes total), almost all of it has been sewn back together. However, the most recent discovery of missing parts was in 2010, which means that most DVD releases are missing huge amounts of the complete film. If you want to see this film in its most complete form, seek out Kino’s The Complete Metropolis DVD/Blu-Ray release, which includes all of the 2010 footage, a restoration of the original film score, and some nice extras about the restoration.

SHERLOCK, JR. (1924, dir. Buster Keaton): I’m pretty sure any silent film primer must include a Buster Keaton film; the only debate is which one. Most people would probably list The General as Keaton’s most outstanding feat, and I agree that The General is pretty much perfect. However, if you want to understand how mind-bendingly clever Buster Keaton could be, there is no finer showcase than Sherlock, Jr.

Buster Keaton was a master of both comedy and stunt work. At the most basic level, almost all of his films are some variant of a stone-faced-boy-woos-girl plotline, but every extraordinary contraption needs a firm skeleton as a base. It is on this simple framework, Keaton strings together extraordinary visual gags, feats of deft comic timing, and death-defying stunts, all in the name of entertainment.

Sherlock, Jr. is an excellent example of this. For most of the film’s running time, Keaton is up to his usual antics. However, the coup de grace of the film is the closing sequence, which is a hallucinogenic, perfectly timed, meticulously choreographed film-within-a-film sequence, where Keaton is suddenly reacting to the film edits themselves. It’s a jaw-dropping piece of filmmaking, especially when you realize that every single gag had to be made in-camera: traveling matte (blue screen) effects wouldn’t be invented until the late 1930s.

Sherlock, Jr. is currently available on Netflix Streaming, but if you really want a treat, track down Kino’s restoration on Blu-Ray. It’s beautiful, and also includes Keaton’s Three Ages.

THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925, dir. Rupert Julien): One of the great ancestors of the modern horror film, The Phantom of the Opera may seem tame today in terms of shock value, but still holds a hypnotic sway with viewers. Beautifully shot and anchored around a legendary performance by Lon Chaney, Sr., The Phantom of the Opera is a fine old-school monster film.

Something that will likely surprise most viewers is the fact that some of the film is in color (assuming you are seeing a good print). In fact, The Phantom of the Opera utilizes no less than three different kinds of color filmmaking: early two-strip Technicolor (seen in the image above), Prizmacolor, and Handschiegel (during which stamps were used to hand-color prints). There was also hand-tinting of various prints. The overall result is dreamlike and gorgeous.

Beware of cheap prints of this movie. If you want the full effect of this film, I suggest tracking down the Milestone Collection Ultimate Edition DVD, which includes the 1925 original version (this is the one to watch), the 1929 restoration (which has sound and adds some scenes that were shot later), plus a whole slew of extras.

CITY LIGHTS (1931, dir. Charlie Chaplin): Like Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin is a must-have on a silent film primer. Much has been written regarding comparisons between these two early giants of cinema comedy; Keaton is something of a populist everyman compared to Chaplin’s balletic richness. Chaplin’s comedy is often layered over an undercurrent of social commentary, which sometimes gives the film depth… or sometimes makes the film feel preachy. Who is the greater comedian is a matter of personal taste, but both men were true artists.

City Lights features Chaplin’s iconic character, The Tramp, who has fallen in love with a blind flower girl. The Tramp befriends a rich benefactor, and through various machinations, is able to become the benefactor for the woman he loves. This structure allows for a lot of commentary on the economic times of the early 1930’s. Keep in mind that this film was made just a couple years after the 1929 stock market crash, so what you are seeing on film here is the early Great Depression. Beyond that, though, it’s a sweet little love story, with an ending that lunges unabashedly at your soft squishy bits.

I’ve yet to see a truly stellar print of this film for sale, but since The Criterion Collection just released an amazing edition of Chaplin’s Modern Times on Blu-Ray, one can hope that City Lights will eventually follow. In the meantime, you can see City Lights as part of the Criterion Collection’s array of streaming offerings on Hulu Plus, or you can snag a nice giant box set of Chaplin films that was released by Warner Home Video about eight years ago.

THE ADVENTURES OF PRINCE ACHMED (1926, dir. Lotte Reiniger): This film is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen on a screen. It is also one of the earliest feature-length animated films, wherein each of the 96,000 frames were hand-crafted out of paper cutouts, all done by one woman by the name of Lotte Reiniger.

The film is pure magic. The design is gorgeous, consisting merely of ornate silhouettes and hand-tinted color. The story, full of mythical creatures and adventure, is the sort of thing that will enchant children as well as adults. I first saw this in the comfort of my own apartment, but I’ve heard tales of entire theaters full of children, held in rapt attention by this movie.

The Milestone Collection has a very nice DVD release for this feature, but sometimes nice streaming prints pop up on Netflix Streaming or Hulu Plus.

SAFETY LAST! (1923, dirs. Fred C. Newmeyer and Sam Taylor): Safety Last! is a very early comedy that features Harold Lloyd, who never quite reached the heights of fame inhabited by Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. However, that’s not to say he’s a lesser performer; much of his obscurity is due to the fact that prints of his films were carefully guarded by his family in the modern era, meaning that much of his work went unseen for decades. The good news about this situation is that those prints are currently in excellent condition, and have recently been made available on DVD.

Roger Ebert noted in his Great Movies entry on this film that Lloyd didn’t quite have the natural comedy genius that Keaton or Chaplin had; instead, Lloyd got the same effect through sheer gumption, toil, and sweat. Safety Last! is the best showcase of his work that I’ve seen, and definitely the one that has become most iconic. (If you saw Scorsese’s Hugo last year, you’ll recognize aspects of the clock tower scene seen in the image above.)

Lloyd’s films are a bit like Keaton’s, in which they usually have a basic love story at the center, surrounded by Lloyd’s antics and stunt work. And as a stuntman, Lloyd was as ballsy as Keaton. At the pinnacle of Safety Last! is a dizzying climb up a clock tower, which Lloyd did almost entirely itself, on a real skyscraper, while in possession of only one thumb and seven fingers. The clock tower feat is genuinely unsettling (and quite funny), even after all these years.

Are you hooked yet? Great! Here are some more silent films that you might enjoy:

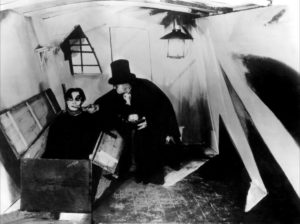

THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920, dir. Robert Weine): This amazing German expressionist horror film makes ingenious use of hallucinogenic, mind-twisting paper sets.

THE LODGER (1927, dir. Alfred Hitchcock): Hitchcock’s best-known silent film is a Jack the Ripper tale, which shows early hallmarks of Hitchcock’s visual flare.

FAUST (1926, dir. F. W. Murnau): This adaptation of Goethe’s deal-with-the-devil tale is a visual treat from one of the greatest directors of the silent era. Modern audiences in particular get a kick out of the portrayal of Mephisto. If you like this, also make sure to check out Murnau’s other films, particularly Nosferatu, Sunrise, and The Last Laugh.

THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC (1928, dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer): This one might test your patience a little, but it’s definitely worth a watch. Dreyer makes amazing use of minimalist sets and extreme close-ups. If you can, locate a copy that is accompanied by Richard Einhorn’s fantastic musical composition, “Voices of Light”.

MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929, dir. Dziga Vertov): I adore this movie. The only reason I didn’t put it in the main list is that this film is fairly avant-garde. This film is simply a string of camera shots, taken on the streets of urban Russia, strung together by visual relationships instead of a narrative. The film showcases a dizzying array of editing tricks and visual stunts. It also serves as a documentary about life in Russia in 1929, but it’s an impressionistic one. If you care to check it out, I suggest watching it with a stunning score written by the Alloy Orchestra, which is something you can do right here on YouTube.

Do you have any silent favorites? Put them in the comments!

I’m personally a sucker for ‘Broken Blossoms’ as well. Melodrama and racial stereotypes, sure, but also Lillian Gish. Everybody loved Mary Pickford, but give me Lillian Gish any day. (Including as Alan Alda’s off-the-deep-end mother in ‘Sweet Liberty’!)

What, no love for “Sunrise” or Colleen Moore..?

Sunrise is mentioned under Faust. Also, as I said, this isn’t a “best of” list.

Oh, theeeeerrre it is!

“The Thief of Bagdad”, with Douglas Fairbanks, then? Gotta have some Doug Fairbanks.